6 Types of Competitive Advantage

6 Types of Competitive Advantage

Durable Value’s process specialises in the competitive advantages that leading US investors have found to underpin all successful listed companies.

What are the reasons behind the 6 Competitive Advantages being central to strategy and success?

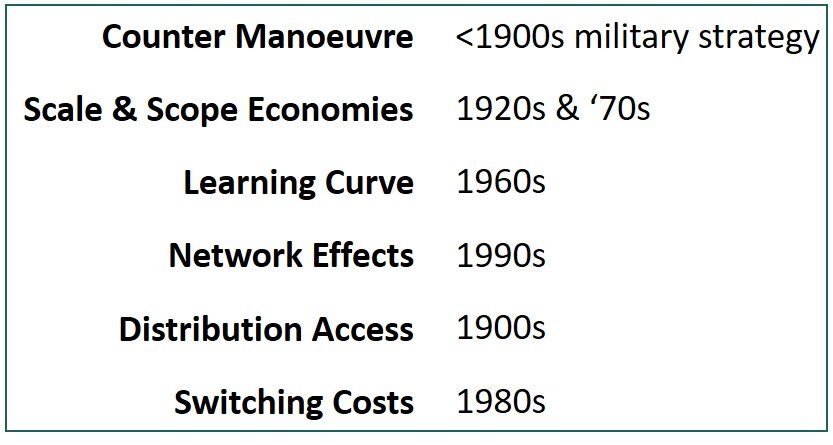

Established origins.

The 6 Competitive Advantages have long been known about, as they are largely rooted in unchanging microeconomics. Consequently, they apply equally to tech start-ups as they do to firms that are centuries-old.

The 6 Competitive Advantages have long been known about, as they are largely rooted in unchanging microeconomics. Consequently, they apply equally to tech start-ups as they do to firms that are centuries-old.

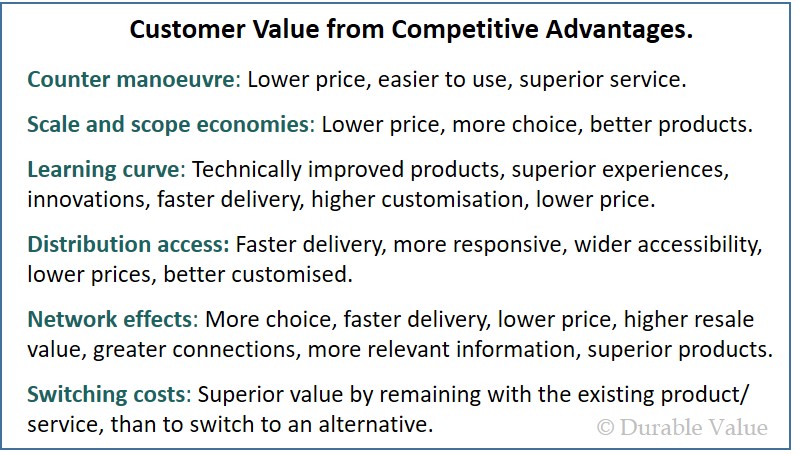

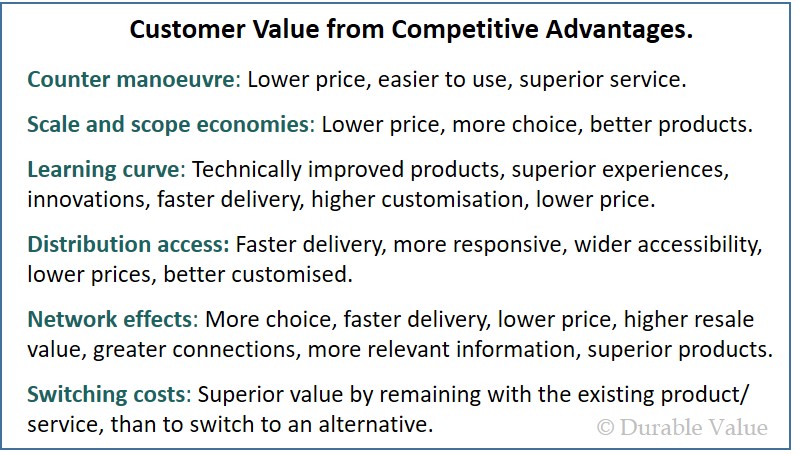

Drivers of superior customer value.

Their early identification was due in part to their ability to deliver significant customer value, and at a fundamental level that spanned industries and diverse market needs. (Click to enlarge).

Their early identification was due in part to their ability to deliver significant customer value, and at a fundamental level that spanned industries and diverse market needs. (Click to enlarge).

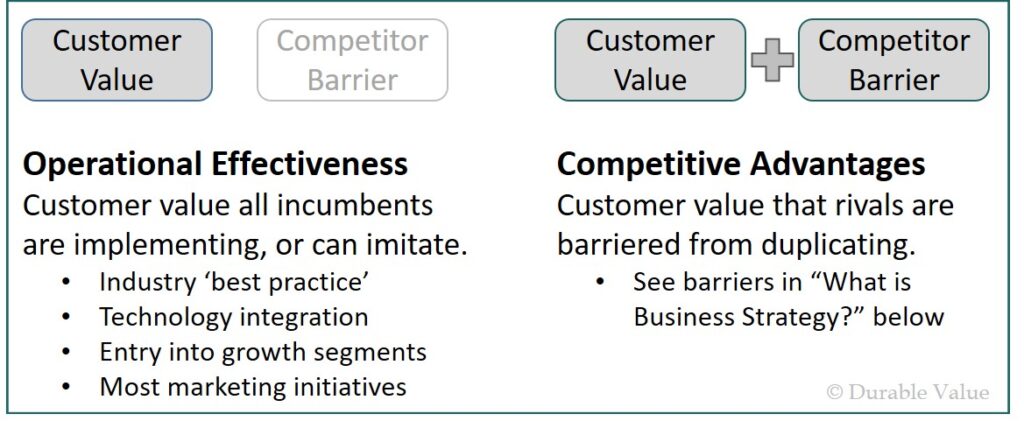

Unmatchable value.

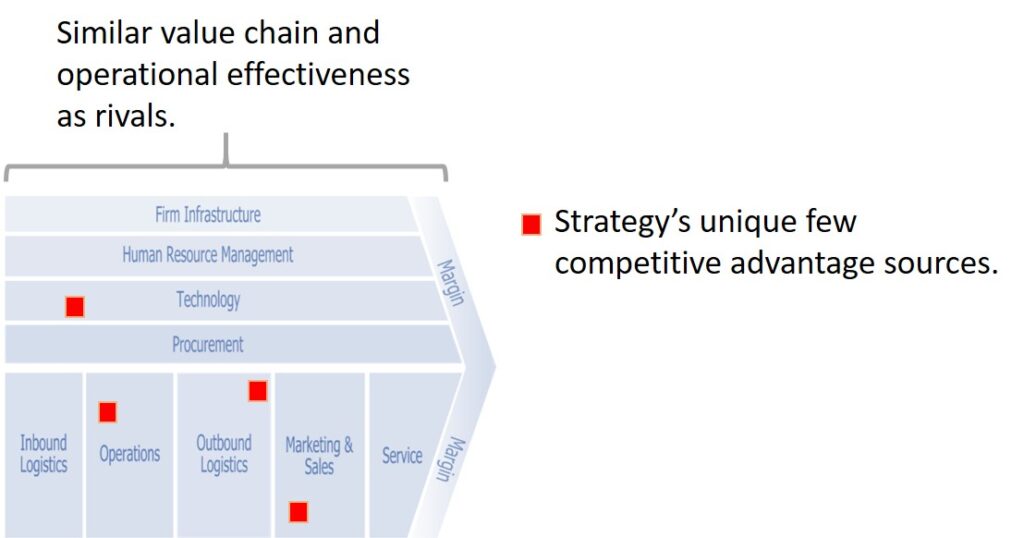

Crucially, the 6 Competitive Advantages deliver superior customer value over rivals; ‘superior’ because rivals face barriers to securing the Competitive Advantages themselves (see ‘What is Business Strategy?’ below). This barrier distinguishes Competitive Advantages from operational effectiveness that a majority of business initiatives fall into. (Click to enlarge).

Crucially, the 6 Competitive Advantages deliver superior customer value over rivals; ‘superior’ because rivals face barriers to securing the Competitive Advantages themselves (see ‘What is Business Strategy?’ below). This barrier distinguishes Competitive Advantages from operational effectiveness that a majority of business initiatives fall into. (Click to enlarge).

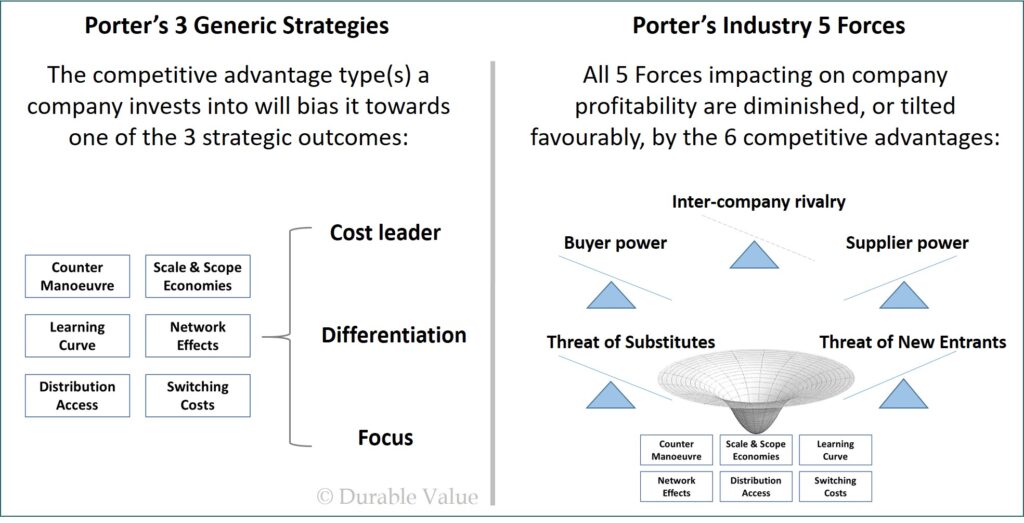

Grouped together by two leading authorities.

The strategy guru Michael Porter was the first to gather them together in 1980, identifying 4 of the 6 Competitive Advantages as ‘barriers to entry’.

The strategy guru Michael Porter was the first to gather them together in 1980, identifying 4 of the 6 Competitive Advantages as ‘barriers to entry’.

Soon after, the investor Warren Buffett began using the term ‘moat’ to describe how these Competitive Advantages- like a castle’s moat- act as a barrier protecting a company’s excess returns from being competed away by rival entry.

Both have since become synonymous with competitive advantages/ ‘moats.’

Growing shareholder value.

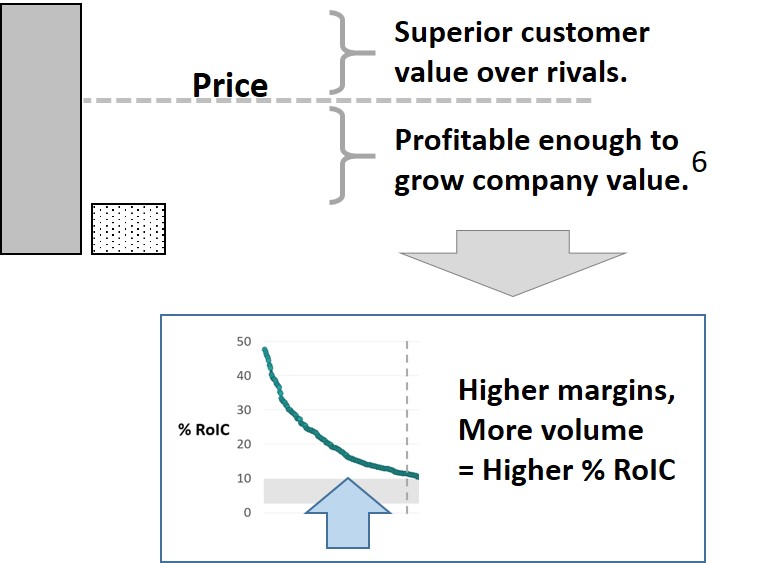

By delivering superior customer value that rivals cannot match, the 6 Competitive Advantages generate high profit returns on invested capital (RoIC) above and beyond the maintenance needs of the capital base.

By delivering superior customer value that rivals cannot match, the 6 Competitive Advantages generate high profit returns on invested capital (RoIC) above and beyond the maintenance needs of the capital base.

This generates cash flow and growth in business value- see ‘How the 6 Advantages drive financial performance’ below.

Proven in the largest business ‘laboratory’- stock markets.

Attracted by these high returns, leading US equity investors have further distilled the Competitive Advantages, by analysing over 1,000 companies generating high RoIC from a sample of over 10,000 US listed equities.

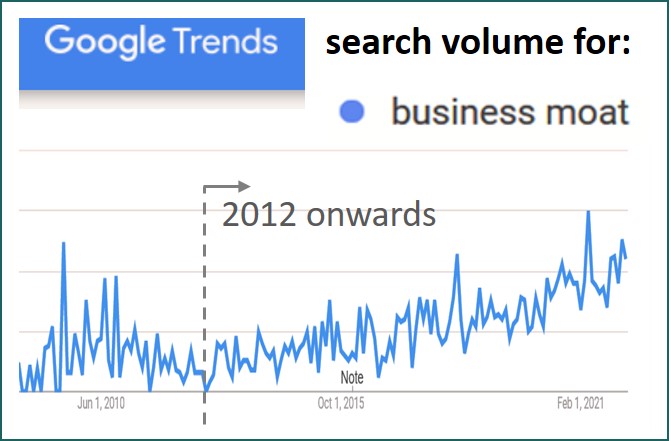

Competitive advantage ‘moats’ reach mainstream investors.

The investment industry is increasingly focussing on whether listed companies have a Competitive Advantage ‘moat’ or not, to identify and profit from those businesses capable of generating positive cash flows for longer than the stock market presently anticipates.

The investment industry is increasingly focussing on whether listed companies have a Competitive Advantage ‘moat’ or not, to identify and profit from those businesses capable of generating positive cash flows for longer than the stock market presently anticipates.

In turn, stock markets become more efficient at valuing companies.

Shaping the most enduring structures in strategy.

The 6 Competitive Advantages’ impact on company profitability is reflected by how they influence the strategy profession’s most referred to frameworks: Michael Porter’s 3 generic strategies and industry 5 forces.

The 6 Competitive Advantages’ impact on company profitability is reflected by how they influence the strategy profession’s most referred to frameworks: Michael Porter’s 3 generic strategies and industry 5 forces.

(Click to enlarge).

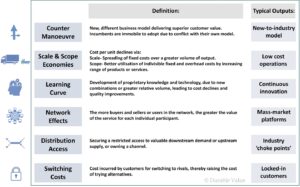

A robust model of Competitive Advantages.

The above factors have led to a model that is exhaustive in identifying all the main types of Competitive Advantage, as shown by no seventh advantage having emerged in the last 20 years, despite technological advances. This completeness is underlined by the Competitive Advantages far-reaching definitions and ubiquitous outputs in the table.

The above factors have led to a model that is exhaustive in identifying all the main types of Competitive Advantage, as shown by no seventh advantage having emerged in the last 20 years, despite technological advances. This completeness is underlined by the Competitive Advantages far-reaching definitions and ubiquitous outputs in the table.

(Click to enlarge).

Durable Value’s process is built around the 6 types of Competitive Advantage, to offer two services:

- Strategy formulation that helps companies gain 1 or more of the Advantage types, and

- For companies already with a Competitive Advantage, growth expansion that leverages the 6 Advantages.

Related articles

.

What is Business Strategy?

Starting from a ‘level playing field.’

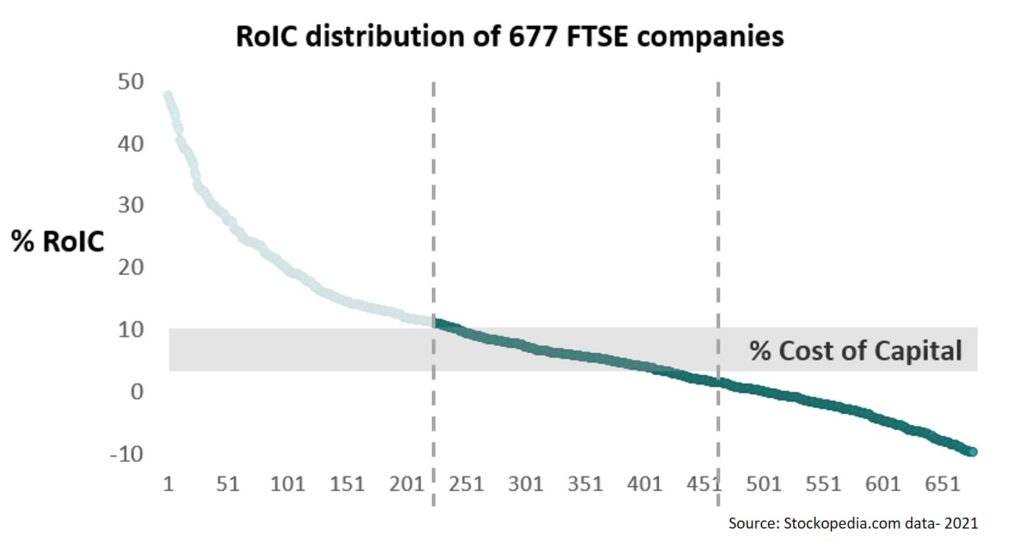

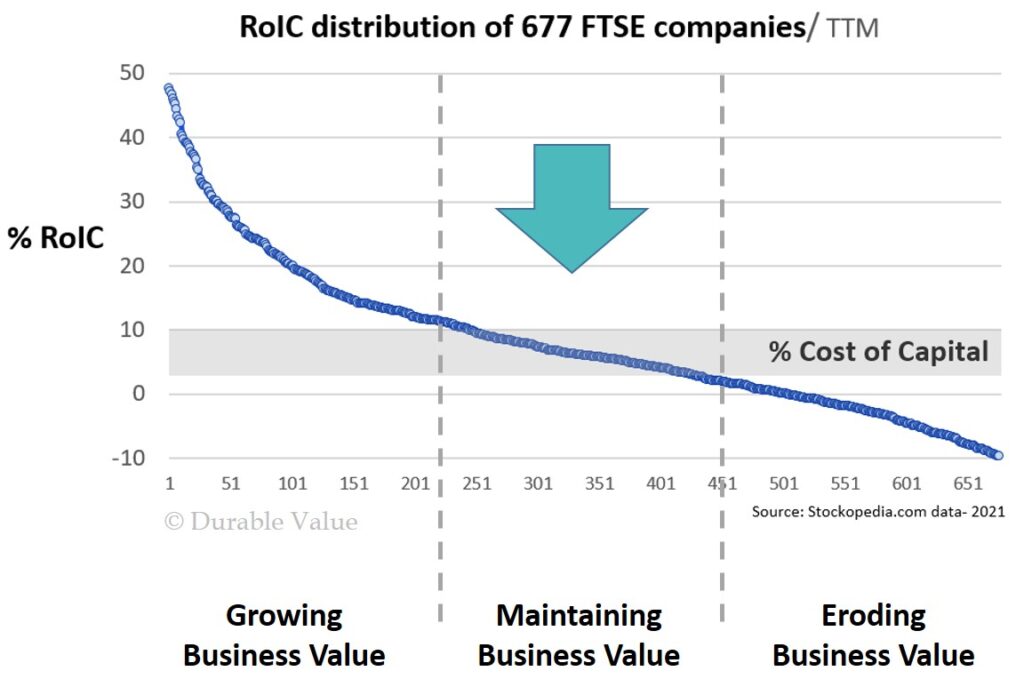

Business strategy and competitive advantages are best explained from a point of nil competitive advantage. This is a situation faced by broadly 2/3rds of companies, resulting in their 5yr average % Return on Invested Capital to match or fall below their cost of capital¹:

For these companies without a competitive advantage, focussing on operational effectiveness ensures that most can remain relevant and viable.

“[In] markets where no companies enjoy a competitive advantage, the only option here is to focus relentlessly on operational effectiveness.”

Bruce Greenwald- Professor at Columbia Business School.₂

How can a competitive advantage and higher RoIC be attained?

To move into the top 1/3rd of RoIC performers requires an operationally effective company to develop a strategy:

“Operational effectiveness is… doing the same things as your competitors.

Strategy is on top of operational effectiveness… Strategy is building the choices that are going to define your uniqueness in the business.”

Professor Michael Porter.³

Graphically this statement can be represented as:

(In terms of operational effectiveness, digitalisation is the 2020’s equivalent to TQM, Six sigma, JIT, BPR etc. in the 1990s. All companies in a sector are implementing broadly similar digital changes).

Specifically, a strategy can be defined as:

“A plan of action to develop a Competitive Advantage and compound it.”

Bruce Henderson- founder of McKinsey consultancy.₄

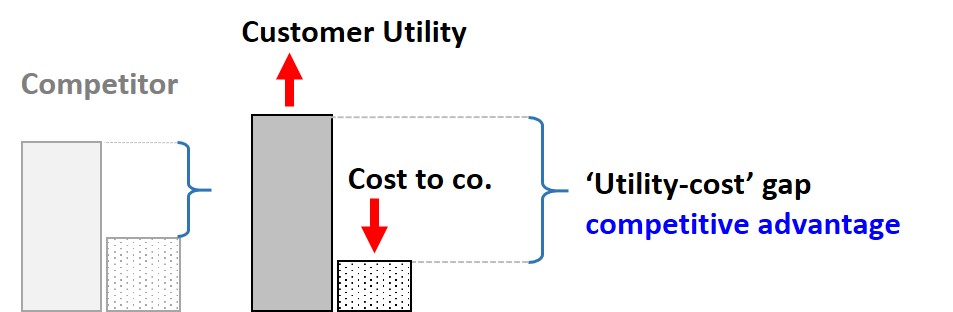

With the competitive advantage itself being the value a firm is able to create for its buyers that exceeds the firm’s cost of creating it.₅ Specifically, a competitive advantage is a widening of the gap between customer usefulness ‘utility’ and the cost to the company, as to exceed that of rivals.

From this wide utility-cost difference, price can then be set to deliver both superior customer value AND be sufficient profitability as to increase RoIC and grow shareholder value:

This utility-cost ‘gap’ can be determined by adding:

– Measures of customer value (e.g. customer purchase frequency, customer satisfaction score, customer loyalty duration, net promoter score etc.),

with

– Measures of product profitability (e.g. customer lifetime value, threshold profitability₆, gross margin etc.).

A product/ service underpinned by a competitive advantage will deliver both high customer vaue and high profitability.

Strategy as ‘how’ to compete and ‘where’ in the market.

To achieve a competitive advantage in widening this utility-cost gap, a company invests in assets, capabilities or market positions of value to a defined target segment. ‘Of value’ because these resources either generate greater customer ‘utility’ usefulness over rivals, or lower the company’s cost in serving the needs of that segment.

The defined target segment is the “where” a company chooses to compete, the unique assets, capabilities or market positions as sources of competitive advantage are the “how” it competes, in better serving that target over rivals.

These resources frequently bias towards either the customer utility side to deliver a superior ‘differentiated’ proposition, or the cost side and a ‘lowest cost’ cheaper proposition.

Sustained advantages that are protected from rival imitation.

Importantly, these should be unique resources that no rivals have secured, or are much further behind in harnessing each resource relative to the company.

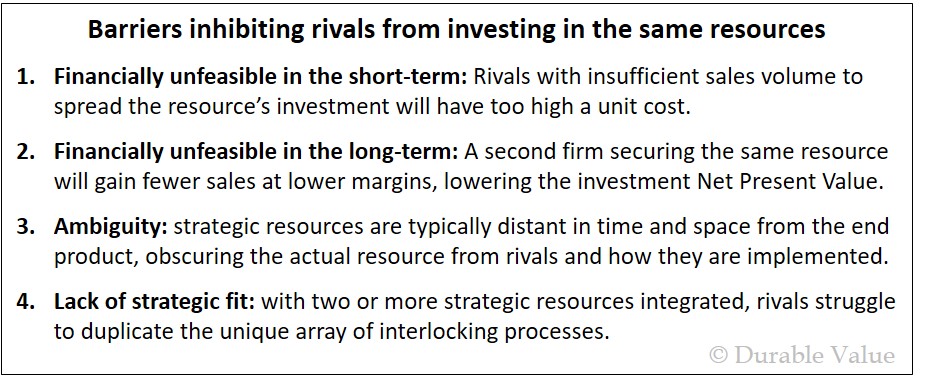

By ensuring that the resources are derived from one of the 6 competitive advantage types, the resources can deliver a sustainable competitive advantage because they:

-

- Not only increase customer value, but can also

- Remain uniquely owned by one company for a sustained period of 3+ years, due to various barriers:

- Not only increase customer value, but can also

These barriers are critical for a strategy to be successful, for without them rivals will be able to enter market opportunities earning high returns on invested capital, until all excess returns are competed away.

Maintaining a focus on strategy execution over time.

To gradually develop and compound a competitive advantage, the company:

- Implements the core ‘where compete’ and ‘how compete’ strategy by:

-

- making investments in securing the unique assets, capabilities or market positions as sources of competitive advantage, and

- coordinating the vital function-level strategies to support the core strategy (marketing, operations, HR, tech etc.), and

-

- Sustains focus on executing the above by building around this core strategy the vision, objectives, metrics and systems:

Over time, as the company notably excels at and reinvests into the unique assets, capabilities or market positions driving the competitive advantage, they become known as ‘strategic resources’ or ‘core competencies.’ They nevertheless all reside within the 6 Competitive Advantage types. The result is an escape from the clutches of inter-rival mediocrity and maintaining business value, and into the realm of loyal customers, dominant market share and company value growth.

This explains the fundamentals to what a strategy is and how competitive advantages develop.

.

How the 6 Advantages aid Marketing.

Marketing’s struggle to escape rival imitation.

In a majority of companies, marketing faces challenges such as: generating traffic and leads, creating growth on a tight budget and producing higher RoI to demonstrate its value. Let alone build a brand.

These challenges are believed largely due to one factor- the inability to significantly differentiate a company’s value proposition from rival alternatives. For immediately any marketing actions appear successful, competitors quickly copy them and converge on their moves. Imitation borne out of a need to protect market share, meet customer expectations and pile into seeming opportunities. Benchmarking as a way of life.

“When it is really hard to differentiate from others… then you have to compete ferociously to maintain a difference of one sort or another, which is often more imaginary than real.”

Peter Thiel- founder of PayPal, Venture Capitalist & author.¹

The solution is outside of Marketing’s consideration.

Although the 6 types of competitive advantage all deliver customer value that rivals are obstructed from matching- and thereby enables significant differentiation- Marketing scarcely ever mentions them:

The reason for marketing’s silence is believed due to the 6 competitive advantages- as investments in assets, capabilities and market positions- being largely beyond the scope of marketing’s:

- Focus: marketing is market-oriented rather than internal, and

- Control and remit: marketing is often limited to marketing communications only.

Yet the 6 competitive advantages have a profound influence on customer value.

And so there is often a disconnect- a blind spot- between marketing and a company’s underlying competitive advantage, presenting an opportunity for improvement.

Three areas to connect Marketing with a company’s Strategy and Competitive Advantage.

1. Integrating marketing with strategy.

This disconnect presents an opportunity to improve how marketing and competitive advantages interact with each other. Truly ‘strategic marketing’ coordinates multiple target segments/ product lines/ services that share an underlying competitive advantage in such a way that:

- Marketing’s market actions support the competitive advantage’s development by stimulating demand, and in turn

- The competitive advantage makes feasible- and opens up– new market opportunities for marketing to serve.

Answers to these 3 questions will closer integrate marketing with competitive advantages, to the benefit of both:

1. How can marketing best transfer an underlying competitive advantage into superior customer value via the marketing mix? By addressing this, marketing strategies are able to strengthen and prolong the competitive advantage.

2. Should marketing drive for sales volume or margin across different service/ product lines? The answer to this is based upon whether the competitive advantages would benefit from more volume or capital reinvestment (or both).

3. Based on marketing’s intimate knowledge of fundamental customer needs, what new investments could be made into the competitive advantage, so that it can slowly evolve to meet customer needs and deliver better performance than that of competitors? Similarly, what threats in the external environment can marketing identify that call for adjusting/ strengthening the competitive advantage?

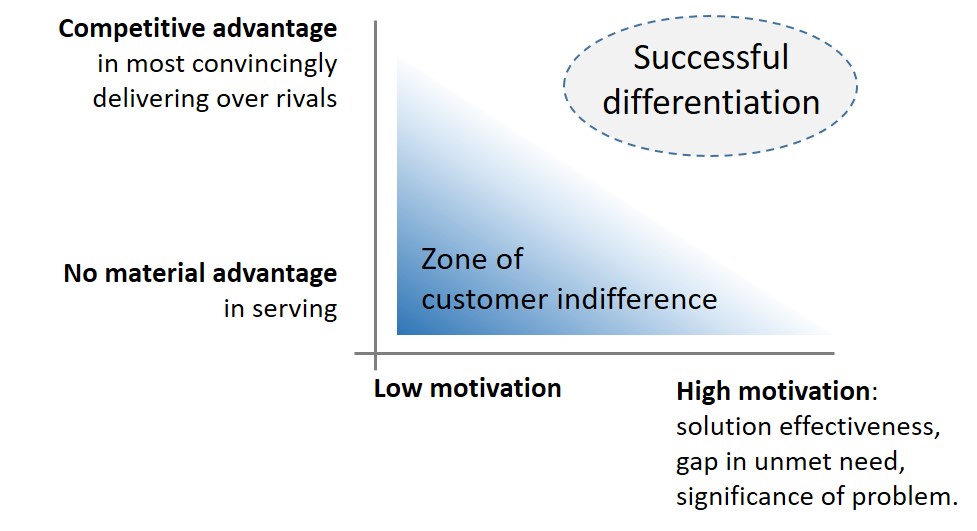

2. Building differentiation that endures.

A second area where marketing can connect with a company’s competitive advantage is how marketing can recast the competitive advantage into customer propositions that meet highly motivating needs, and so achieve sustained differentiation:

Beside enhancing behaviour change, marketing penetration, engagement and loyalty, the most vital outcome of the above is the development of a brand. Brand value as an intangible asset and source of competitive advantage can prolong the underlying advantage from the 6 Competitive Advantage types.

3. Marketing as a source of competitive advantage.

Marketing can also connect with a competitive advantage through marketing itself contributing to the competitive advantage (beyond branding alone). The following are examples of marketing creating sources of competitive advantage:

-

- Market research scale economies- greater expenditure spread over a larger market share, for superior insights over rivals,

- Learning curve & Distribution access – deepen digital consumer experience (CX), to gain access to more data and justify AI investment, for better predictive analytics and CX,Br

- Distribution access- leverage bargaining power to secure exclusive channels for marketing propositions.

These sources of competitive advantage are micro-economic forces. And since marketing’s tools are behavioural economic forces₂ (i.e. psychological forces influencing economic decisions), then the combining of microeconomic with behavioural economic forces can be to powerful effect.

Marketing’s influence within the company.

The above 3 ways in which marketing is able to drive underlying competitive advantages can subsequently increase marketing’s influence to:

-

- Gain Board-level support for marketing moves,

- Secure a larger budget, and

- Make longer term strategic decisions to the benefit of the competitive advantage and therefore consumers alike, instead of short-term tactical moves of limited effectiveness.

This article aims to highlight how strategy’s competitive advantages and the marketing function can greatly benefit each other, towards their shared goal of delivering superior customer value over alternatives.

.

How the 6 Advantages drive financial performance

Business success attracts competition, causing profits to be competed away.

Companies generating high economic returns will attract competitors keen to take a lesser, albeit still attractive, return. Immediately a second company copies a strategic move (e.g. targeting a segment, a new product), any excess gains the original company enjoyed are competed away to a reduced level. This is the economics of supply and demand equilibrium.

With two companies now competing in a broadly similar way, competition leads to prices dropping, margins to fall and fewer sales into the same asset base for lower asset turnover. This causes their profit Return on Invested Capital (RoIC) to fall closer to their Cost of Capital (CoC)¹; the equivalent to a ‘level playing field’ or perfect competition.

Consequently, both companies broadly sit in this performance zone:

The 6 competitive advantages can lead to monopoly-like profitability.

A % RoIC spread above cost of capital is achieved when a company creates a customer demand for their product that is greater than the constrained supply of one company- themselves- producing the product.

Since the 6 types of competitive advantage deliver customer value that is barriered from rival imitation, the competitive advantages are demand and supply-shaping forces that enable setting price and supply to maximise market share gains and/ or profit (to below a margin level that might otherwise provide an ‘umbrella’ for new entrants). This raises % RoIC above its cost of capital and closer to monopoly-like pricing power of 12% to 30+%.

The 6 Competitive Advantages’ ability to prevent the excess profits from being competed away by rival entry is what distinguishes them from operational effectiveness, which has no barriers to emulating and therefore is performed by all companies, ensuring that no excess profit is possible.

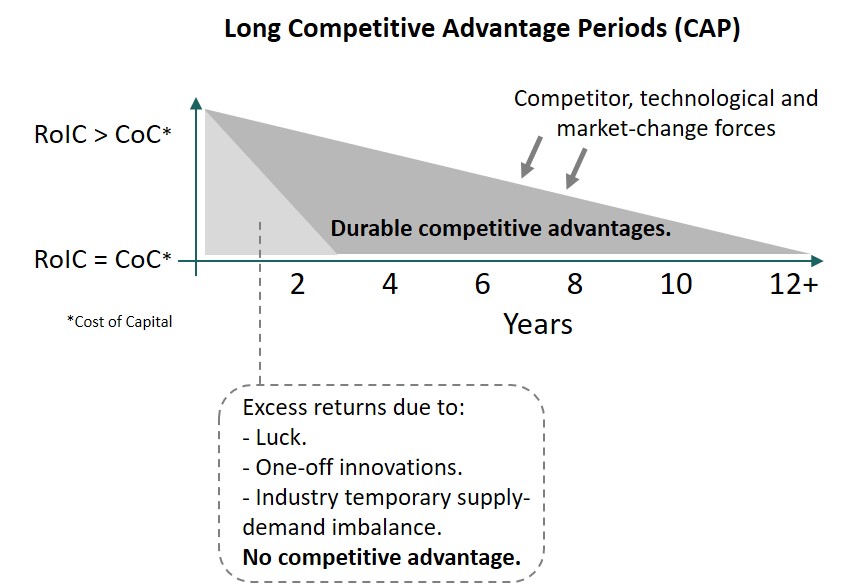

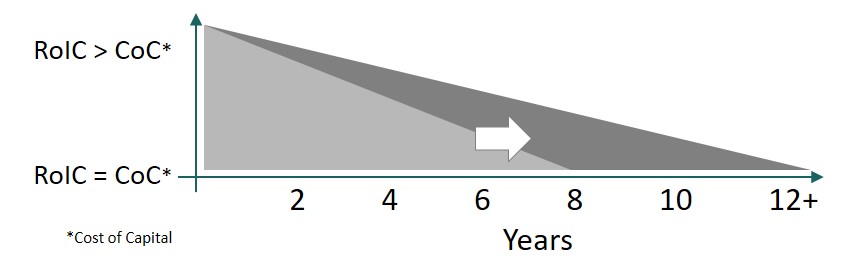

Barriers leading to ‘competitive advantage periods.’

What particularly drew investors’ attention to studying Competitive Advantages is not only the excess profits they generate, but also the duration of the CA and their excess profits over multiple years.

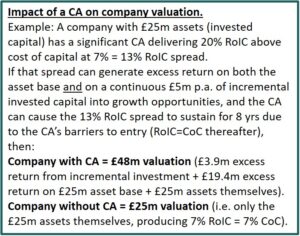

This duration of a Competitive Advantage is termed its ‘competitive advantage period’ or ‘CAP’, as the period it is expected to generate excess profits. In strategy terms for a business owner, the 6 Competitive Advantage types were identified as causing excess return periods lasting from 3 to 25+ years. Any excess return (RoIC>CoC) of less than 3yrs is not considered to be a sustained competitive advantage, and instead caused by other temporary factors:

“Warren Buffett… buys businesses with high returns on capital that have “deep and wide moats”- sustainable competitive advantage periods (CAPs)- and holds them “forever”- hoping that the CAPs stay constant.”

Michael Mauboussin- “CAP- The neglected value driver.”

Since the litmus test for a successful strategy is whether it creates shareholder value, the focus by investors on RoIC>CoC and duration led to their identifying the strategic measures that actually raised shareholder value, sifted away from all the ‘noise’ that only claimed to do so.

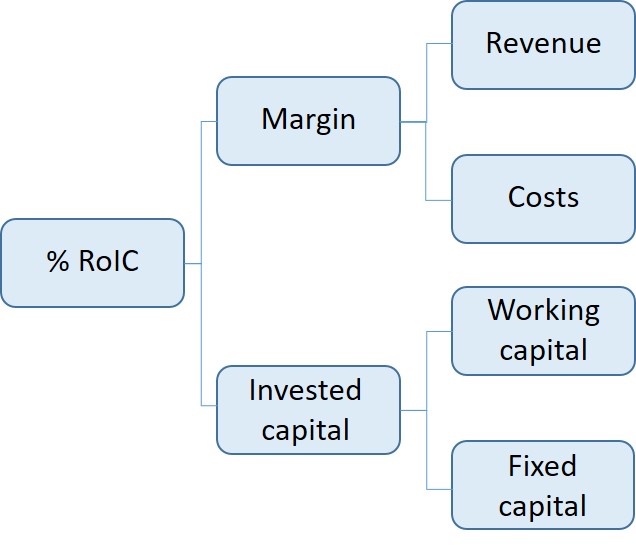

The 6 competitive advantages influence financial drivers to RoIC.

Competitive Advantages influence all the disaggregated parts to RoIC:

- Competitive Advantages raise revenues via greater demand for the superior customer value (including via a price penetration strategy),

- Cost-lowering Competitive Advantages serve to reduce cost per unit sold, such as through scale and scope economies, learning curve and counter-manoeuvre,

- Competitive Advantages can negotiate favourable account receivable and payable terms to lower working capital, as a result of greater bargaining power, and

- Competitive Advantages lower fixed capital as a result of the advantage as investments in assets/ capabilities/ market positions being light in capital intensity, relative to the sales and margin generated.

Higher RoIC translates into greater free cash flow.

We can see from the above breakdown of RoIC how Competitive Advantages also increase free cash flow, especially when assets depreciated off the balance sheet are still driving margins and sales (e.g. brand).

For whilst RoIC is a historic measure and free cash flow is a future-oriented economic profit, a RoIC spread over cost of capital will over time generate surplus net operating profit after tax, beyond reinvestment needs. This generates free cash flow that can either be reinvested or removed from the business, without impacting its competitive position or volume sold.

Managing the 3 drivers of company value.

The lifetime value of a company can be calculated by₄:

These 3 drivers hold true regardless of whether cash flows (e.g. Discounted Cash Flow) or economic profits (e.g. Economic Value Added) are used to determine company value, since both measure the same goal.₅

The reason why the 3rd driver- duration of RoIC spread- is key to business value is due to the power of compounding. For example, a company that produces 15% RoIC for 30 years is worth more than a company producing 30% RoIC for 5 years and 10% RoIC for the remaining 25 years, all else being equal.

And so whilst it is common for companies to overextend growth to maximise the ‘invested growth’ driver, this often leads to competing in too many diverse markets with multiple rivals, leading to confusion over strategy, higher overheads and bureaucracy.

All are forces that conspire to undermine a competitive advantage, shorten its duration and collapse RoIC back down to CoC. A common theme in business.

Instead of maximising invested capital with growth, arguably the most successful capital allocator- Warren Buffett- advises to primarily strengthen the competitive advantage (and subsequent RoIC spread) in order to increase its duration, which can in turn increase investable capital accommodated:

When our long-term competitive position improves… we describe the phenomenon as “widening the moat [competitive advantage].”

We always, of course, hope to earn more money in the short-term. But when short-term and long-term conflict, widening the moat must take precedence.

Warren Buffett- 2005 Berkshire Hathaway annual letter to shareholders.

In following this advice, the competitive advantage and its RoIC can extend for additional years:

The end result is a maximising of a business’ long-term value for its owners, achieved with a wide competitive advantage delivering superior product propositions that satisfy customers, and in a socially/ environmentally-responsible manner.

Footnotes:

The 6 types of Competitive Advantage

¹ First quote: A Dozen Lessons for Entrepreneurs- Tren Griffin (2017). Second quote: 2007 Berkshire Hathaway annual letter.

What is Business Strategy?

¹ Except for start-ups with potential CAs and investing heavily, a minority of companies with part of the company CA’d but the rest is operationally inefficient as to dwarf the overall returns).

₂ Bruce Greenwald and Judd Kahn. Competition Demystified: A radically simplified approach to business strategy.

₃ Professor Michael Porter’s speech- “What is Strategy?” (at 33 mins): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tyUw0h5i9yI&t=1921s

₄ Bruce Henderson- ‘The Origin of Strategy’ (1989)- HBR: http://web.abo.fi/fak/esf/fei/studier/material/hendersonhbr.pdf

₅ Michael Porter (1980) “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.”

₆ To be ‘Profitable enough to grow company value’ requires a profit margin that exceeds the “threshold margin” where RoIC=CoC. If prices are dropped causing the profit margin to fall below threshold margin, then the product may still be profitable and yet destroy shareholder value too, as it earns profit below the total costs (including cost of assets needed to deliver the sale).

To calculate threshold margin = (incremental investment in assets per £1 sales %) x (Cost of capital)

(1+ Cost of capital) x (1- tax rate)

Example:

(40p additional investment in assets per £1 extra sales) x 7%

(1 + 7%) x (1 – 30% corporation tax rate)

= 0.4 x 0.07 = 0.028 = 3.7%

1.07 x 0.7 0.75

How the 6 Advantages aid Marketing

¹ Peter Thiel- “Competition is for Losers.” At 45 mins: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Fx5Q8xGU8k

₂ “The marketing 4Ps are demand-shaping forces and should be part of basic economic theory… ‘Behavioural economics’ [psychological factors influencing economic decisions] is just another name for ‘marketing’ and what marketing has been researching for 100 years.”

Philip Kotler- Professor of Marketing at Northwestern University’s Kellogg Graduate School of Management. Source: https://vivekkaul.com/tag/philip-kotler/

How the 6 Advantages drive financial performance

¹ Unless both have enjoyed high barriers to entry protecting them from new entrants over multiple years, enabling a mutually profitable co-existence to develop.

₃ Professor Paul Johnson and Professor Michael Mauboussin. “CAP- The neglected value driver.” http://people.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/pdfiles/eqnotes/cap.pdf

₄ Since the value of a company is the sum of its lifetime discounted cash flows, the size of these net cash flow is driven by RoIC spread, duration of spread and the amount of capital that can be invested at such spread (see Aswath Damadoran- NYU-http://people.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/pdfiles/eqnotes/ValMat.pdf).

Specifically, Economic Value Added (EVA) shows how these 3 drivers relate to DCF, since projected EVA leads to the same valuation as DCF.

EVA = Net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) – (Invested Capital*Cost of Capital).

The bracketed part refers to the investable capital.

The RoIC spread drives the NOPAT side (due to higher margin and faster rate of profit growth) as well as reducing invested capital needed to create that NOPAT and thereby lowering the finance charge (as Invested Capital*Cost of Capital) that would otherwise be deducted from that NOPAT.

And the company seeks to extend positive EVA annually for as many years as possible, which is the duration aspect of DCF.

₅ Projected EVA leads to the same valuation as DCF. See Aswath Damadoran- NYU- http://people.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/New_Home_Page/lectures/eva.html